Blog #15 Trauma Part 3: Trauma and Your Body

- Rex Tse

- Nov 11, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Nov 13, 2025

No, It Is Just in My Head

Jun is a Mandarin speaking Chinese American man in his 40s living in San Francisco, California. He arrived at a local mental health clinic wanting to do something about his insomnia, lack of motivation, and body pain. He originally requested a female therapist, but since the facility didn’t have any openings from its female clinicians, he ended up seeing a male therapist who also happened to be of Chinese descent.

During the first session, the therapist adhered to the proper procedures; he asked him a series of questions, including family life, family history, and trauma history, trying to discover the core issue. Despite noticing Jun’s heavy and burdened posture and facial expression, he did not disclose any significant past issues or difficult histories. Baffled by this presentation, the therapist wondered if the cause of Jun’s suffering was purely medical. It turned out Jun just had a physical examination, and told his therapist that “all the blood work came out normal”. Hearing that, the therapist asked, “Who referred you to come to therapy?” Jun replied, “I told my doctor about not feeling well, and since he could not find anything wrong with me, recommended I see a psychiatrist. When I arrived here, they required me to have therapy if I wanted to get on meds. I don’t think I need meds, and I also don’t think there is anything wrong with my head. It’s just that I can’t sleep or get motivated”.

“I see.” The therapist said, sensing a reluctance in Jun. Confident that the root cause was likely mental health related, he requested, “In order to find out more about what caused your body pain and loss of motivation, it might be beneficial if you can commit to three months of weekly therapy. If we truly cannot discover the cause, I can refer you to a specialist”. Jun agreed and started going to therapy every Tuesday afternoon. A few weeks passed, and the meds had some success, and throughout the few therapy sessions, the therapist began to understand more about Jun. Jun worked for his brother in a home renovation business, and it has been an unusually slow summer season. As a result, Jun worried about money. Jun has a wife and two pre-adolescent children. He enjoys spending time with kids, but feels challenged by his strained marriage. At home, he felt like he was either in constant arguments with his wife, or they left each other alone completely. However, Jun’s body pain, and lack of motivation began when he was a young adult. As he described it, “it started up seemingly out of nowhere, and it had been like that ever since.”

Another few weeks passed. Jun began to feel more and more comfortable with his therapist. In one session, he disclosed his childhood. “You know, growing up had definitely been a testing experience,” Jun said. “Sure, parents from the old generation like to show their love by beating their kids, sometimes I wondered if I got an extra dose of loving. Dad used to drink a lot, I mean, a bottle of liquor every day. And when he was drunk, he would beat us up. Usually, he would hit me on my arms and back.” He then points to the areas of his body where he was beaten. “Funny how it is where I feel on and off pains these days.” Being curious, the therapist asked, “Did you see a doctor to rule out old injuries?” Jun replied, “No, I know it isn’t that, I have plenty of old injuries, and this ain’t it. You know, you are not supposed to talk smack about your parents, but what happened, that just wasn’t right. I knew this, so I’d never beat my own kids.”

The therapist nodded with concern, but he also saw an opportunity to explain how trauma impacts the body. He started to present his well thought-out script on trauma and chronic body conditions. However, Jun reacted, “No, it is just in my head. I need to get over it. Those body pains are probably coincidences”. “In terms of how our nervous system works, things are probably not a coincidence,” the therapist said, explaining the connection between mind and body. Jun seemed reluctant, but also couldn’t deny how his lived experience matched up with his therapist’s narrative.

At the end of the three months, the therapist asked Jun about his thoughts on going to therapy. Jun remarked that it had been an “eye-opening” experience. Although he is still working on his body pain, his insomnia and lack of motivation improved with a more comprehensive understanding of why he was struggling. In the last session, the therapist asked, “So, it seems like you are getting something out of therapy, would you like to continue where we can dig deeper into stuff?” Jun replied, “What about the referrals?” The therapist felt a bit confused, only to see Jun burst into laughter. “Just kidding, man. You get to keep your job!”

How Trauma Lives and Changes Us from the Inside

Jun’s story may or may not resonate with all of us. Like Jun, some of us may have long held beliefs that the mind is a separate part from the body, and the mind can be conquered through stoic means. This unfortunately is not reflective of reality.

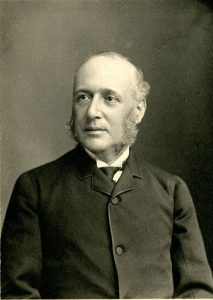

The truth is, the impact of trauma may manifest in a multitude of nuanced ways, especially on our physical health. Unfortunately, due to how entangled psychological trauma is with physical symptoms, it is easy to overlook our emotional states by focusing on our medical issues. Here is a historical example of how trauma was mistaken as medical problems - After the American Civil War, Dr. Jacob Mendez Da Costa studied the health of over 300 soldiers, some of whom “complained of chest pain, a very rapid pulse (one patient registered a pulse of 192 beats per minute!), irregular heartbeats, difficulty breathing, tunnel vision, fatigue and weakness, bad dreams, difficulty sleeping, headaches and more.” (Bowen 2016). Dr. Da Costa thought it was caused by the heart, and called this condition irritable heart, also known as soldier’s heart, and “Da Costa’s Syndrome” by other physicians. The problem was, for patients with an irritable heart, there was no physical evidence of a damaged heart. However, Dr. Da Costa’s work would lay the foundation for eventually our modern understanding of PTSD. All the rapid pulse, chest pain, fatigue and bad dreams of those soldiers were symptoms of psychological trauma.

Image: Dr. Da Costa, www.civilwarmed.org.

Trauma, Stress, and the Body

Our mind/body connection is a very complex system. Ultimately, this system is trying to keep us alive and safe for as long as possible. In order to address our trauma, we need to understand the intricate relationship between our mind and body. In Jun’s story, his mysterious symptoms of stress and pain baffled him for years. While it might be hard to fathom how his childhood traumatic experiences can contribute to his chronic ailments, if we examine the different components of his emotional history, family systems, and habitual coping, we can piece together an idea for why he felt that way.

Trauma activates our autonomic nervous system (ANS), the part of our nervous system that, upon activation, elicits the fight or flight response. When we say we are nervous, on edge, keyed up, stressed, or anxious, our ANS is active. In the previous posts in the series, we have covered scenarios and examples of this phenomenon with my friend, Sue, and Kwanjai. In all three cases, they started to experience fight or flight feelings after their traumatic incidents. What happens is that the body has learned to protect itself through being constantly vigilant, primed to react to the unexpected. The problem is that there is often a huge cost to this hypervigilant response; in order to be constantly primed for reaction, our body has to remain in a stressful state. Here is a diagram that summarizes the impacts of fight or flight physiology (Yetman 2025).

Diagram 1: The physiology of SNS activation from healthline.com

When we are in the state of fight or flight, a part of our nervous system called the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is activated. From the diagram, we can see that it impacts a great variety of bodily functions, from vision, circulation, digestion, to even reproduction. When we are stressed, the SNS activates and prepares the body for action. Your breathing rate increases (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2022) and your blood gets redirected to skeletal muscles, which are primed for intense motor activity (Roatta 2010). Even without further information, we can imagine how a fight or flight nervous system state can put stress on our bodies. Furthermore, if we consider the examples given in this series so far - my friend being triggered on a trip to an Ikea, Sue and her fears around dogs, Kwanjai and the racist lady, and Jun and his mysterious body pain, stresses from traumatic experiences sometimes turn chronic. A chronic fight or flight response places strains on our bodies that might negatively impact our health and well-being. It is easy to conclude that chronic stress due to trauma may affect all parts of the body. For example, it is common knowledge that chronic stress and anxiety can lead to indigestion and, in some cases irritable bowel syndrome. Other health conditions may include and are not limited to heart disease, diabetes, muscle tension, hypertension, stroke, and autoimmune diseases (Mayoclinic 2023, Bucsek et. al. 2018, Galli et. al. 2021, Huffhines et al. 2016)*.

* For those of you who are accustomed to reading scientific literature, I highly recommend reviewing the cited articles.

When the Body Keeps Scores

The linkage between trauma and its impact on the physical body has been well published. One of the more well-known authors on this topic would be Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, who is famous for his book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. In the book, Van der Kolk explains the neurological and emotional experience of trauma and its long-term aftermath. He explains that “trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is also the imprint left by that experience on the mind, brain, and the body”, (Van der Kolk 2014). Like we have previously explored in this post and the last two, trauma has a way to seep into the different aspects of our lives, from altering our worldviews and thought patterns, to creating bodily reactions. Van der Kolk’s book went into the complex neural activities involved in trauma response.

The neurological activation of trauma leads to a cluster of symptoms and experiences that range from fight, flight and freeze when our mind is flooded with flashbacks and horror. We can easily imagine the long-term effects of such experiences being directly or indirectly damaging to the physical body. In order to sustain a chronic stress response, our muscles need to be primed for activity, our digestion slows, which leads to fatigue and GI issues. When our minds are constantly occupied by stress, we may fall behind in our daily activities, leading to underperformance in self-care, social, and job functions. In an interview between Van der Kolk and Dr. Spencer Eth, a doctor who treated survivors of the September 11th terrorist attack, Eth narrated about what was credited to be helpful; they all have to do with working on the body and its sensations - “acupuncture, massage, yoga, and EMDR, in that order”, (Van der Kolk 2014).

One of the most important points of Van der Kolk’s messages has to do with a therapy modality called “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing” therapy, or EMDR. The principle is that by inducing eye movements, we can activate our brain in ways similar to REM sleep. Coupled with bringing up somatic experiences of trauma, we can “unstick” the raw feelings of traumatic reaction, returning us to a calmer psychological state. The efficacy of EMDR is uncontested, with a number of studies showing EMDR as an effective treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (Shapiro 2014) and even depression (Seok and Kim 2024).

However, as a practicing mental health clinician, I would like to point out that there is a caveat and nuance to seeking EMDR as a treatment in general. EMDR, despite having scientific backing, should not be regarded as a trauma “cure-all”. Trauma, in general, requires a comprehensive approach that takes into account different aspects of our psyche. EMDR done in isolation without other interventions might not be effective. One of my supervisors, who had been providing trauma care for a long time, told me a story about how an organization started training EMTs and first responders in EMDR methods for psychological trauma victims on the scene. The result was ineffective, and sometimes countereffective.

It is crucial to seek a mental health professional whom you feel comfortable working with when embarking on the journey of trauma recovery. Professionally, I know stories in which people have benefited from a modality, a clinical way of saying “method”, like EMDR. However, I have also heard of stories in which people experienced little to no improvement, or even worsening of trauma symptoms. With numerous studies and evidence backing the positive effects of therapies like EMDR, it seems baffling that some folks experience the opposite of the supposed benefits. What may be happening could be a great number of factors. For example, EMDR and other trauma therapies require a sufficient amount of ability to feel safe. Not being able to do so will lead to feelings of being overwhelmed and re-traumatized. Another major reason for trauma therapy to be ineffective might be due to the length and breadth of the trauma. For instance, if you have experienced long-term and repeated traumatic experiences, your mind and body might have created many different ways to cope, including maladaptive worldviews, chronic depression and anxiety, or even panic. In those cases, you might need to address the issue from multiple angles instead of only focusing on the trauma reaction itself. The take-home message is that everyone is different, and your trauma recovery might be longer than a few sessions, or a few months; the best way to address our trauma starts with finding a therapist qualified in trauma therapy whom you feel comfortable working with.

Worthy Mentions of Other Major Authors on the Topic

One could argue that The Body Keeps the Score may be the most famous and successful publication on trauma. However, Van der Kolk’s work represented a small corner in his field of subject. With the increasing awareness of mental health, more and more experts are weighing in with their professional knowledge.

Peter A. Levine, PHD, is a clinical psychologist and the author of Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. He created a therapy modality named “somatic experiencing”. The book advocates the idea that trauma is healable, and it can be resolved through working with our body sensations, vacillating between a trauma-activated state and a calm state.

Gabor Mate, MD, is an author who wrote extensively about addiction and trauma. One of his messages centered around how the mind and the body are connected. In his book, When the Body Says No: Exploring the Stress-Disease Connection, he narrated about his clinical experience around how mental health struggles can lead to chronic body ailments, from cancer, heart disease, to diabetes. Some might argue that his claims are over-exaggerated. However, it is an established fact that stress and some chronic illnesses are positively correlated, even if the bigger picture involves more than psychological factors.

The three authors mentioned in this post do not represent the entire research community on the topic of trauma and the body. There are numerous research papers from the past and ongoing ones in the present that continue to push the field forward. I encourage you to be curious about this topic and find the methods that work best for you.

Somatic Approach and Safety of the Body

If there is one thing to take away from this exploration of trauma and the body, it is that as complex, or convoluted as the topic may be, recovery is possible. You don’t need to know the intricate mechanisms of our psyche and nervous system like it’s the back of your hand. The effective way to tackle trauma will be to find safety again in the body relating to our trauma triggers, in clinical terms - we can use a somatic approach to reverse the reactions we developed in the face of trauma.

The word “somatic” comes from “soma”, meaning “body” in the Greek language. Somatic therapy encompasses a number of different methods that involve building an understanding of how your body feels, and subsequently exposing yourself to feelings of calm and safety until your nervous system “gets the memo” that it doesn’t have to react with intense stress. It is like decoupling your association between things that remind you of danger and how the body reacts fiercely. It is important to know that when we are speaking about the somatic approach in psychotherapy, we are not referring to alternative medicines like acupuncture, massage therapy, chiropractic, or even energy work. Although some folks find those alternative medicines to be helpful, it is not somatic therapy. Somatic therapy does not even have to involve touch. In fact, most don’t.

The first step of using a somatic approach is to develop a cautious curiosity towards our body sensations. To start, we seek to increase our understanding of our feelings through naming our sensations and journaling. For example, we know when we are joyous, but can we write about the experience further with detailed descriptions? What about sadness? What about fear? What about peace? In this step, I would highly recommend working with a qualified psychotherapist.

Example: I can identify feeling joy. I notice I feel the joy in my torso, and I can describe my feeling of joy with the words: Light, effortless, expanding. |

The second step is to challenge ourselves to access the body sensations of safety and peace alongside difficult trauma-related body sensations. In this step, we should always consider our “window of tolerance” as it was described in Part One of this series. As long as we can metaphorically put one foot in safety, and the other in the difficult reaction, our brain will start to crosslink the two different mindstates. If our environment offers sufficient safety, our nervous system will be disarmed. By practicing “one foot in safety, one foot in a difficult reaction”, we build the habit of soothing our hypersensitivity to triggers, thus leading to longer-term wellness.

Exercise: A Taste for a Somatic Exercise - Pendulation

This is an exercise that aims to introduce an example of trauma recovery through a somatic approach, and what it can look like. The results of this exercise can vary from individual to individual. Discretion is generally advised. Consult a qualified mental health professional if you wish to explore further about somatic therapy.

1: Preparing yourself.

Find a comfortable place, free of distractions, where you won’t be disturbed.

You may sit, stand, or lie down as long as you can stay engaged with the peaceful surroundings.

Notice the things around you. What do you see, hear, and touch?

2. Entering a mindful state.

Feel both of your feet on the ground. If you are sitting, feel how the object you are sitting on is supporting you.

Perceive yourself in relation to the space. Take a moment to notice what object, sound, or texture feels closest to the idea of “safety”.

Allow yourself to experience the glimpse of “safety” in the body, and allow it to stay with you.

3. Find a pleasant state and touch on a difficult feeling.

Continue to stay in the pleasantness of your environment, find a part of your body, an area no bigger than a coin, that feels neutral.

Continue to stay in the pleasantness of your environment, find a part of your body that resides in a mildly difficult emotion with the intensity of only 2-4 out of 10.

If it feels stronger than a 4, go back to part 2 of the exercise.

4. Stay grounded.

With the mild difficult emotion, keep at least one anchor (the support of the ground, the peacefulness of the environment, a color, or an object that inspires peace).

5. Pendulation and completion.

After contacting the difficult emotion for 5 - 10 seconds. We allow ourselves to fully go back to the pleasant state before we focus on the distress.

Stay in the pleasant state for 20 - 30 seconds.

Reawaken the difficult emotion for another 5 - 10 seconds.

Repeat the cycle of distress/peace for two more repetitions.

At the end of the last cycle, allow yourself to be fully immersed in the pleasant state for as long as you wish, and relax.

When you wish to exit the exercise, look around you and your environment for the last time, and notice how you feel now (do you feel calm, peaceful, relieved?)

Write a few words about the experience if you wish.

Safety Reminders and Tips

Always keep the distress mild for this self-guided exercise, around 2-4 out of 10.

If you become overwhelmed, go back to grounding, or stop entirely.

Over time, you can experiment with extending the number of cycles, or extend the time spent in the exercise. However, it is highly advisable to keep the session short if you have limited experience with this kind of practice.

If you or someone you know is looking for therapy in the state of Colorado, you can reach me by visiting my PsychologyToday profile: HERE, or send an email to info@intorelationshipco.com |

Sources:

American Psychological Association. (2018, April 19). APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/cognition

Bowen, A. (2018, March 24). Irritable heart diagnosis 1862 - Civil War Medicine Museum. National Museum of Civil War Medicine. https://www.civilwarmed.org/irritableheart/

Yetman, D. (2025, July 10). Sympathetic nervous system: Function, anatomy, and importance. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/sympathetic-nervous-system

Bucsek, M. J., Giridharan, T., MacDonald, C. R., Hylander, B. L., & Repasky, E. A. (2018). An overview of the role of sympathetic regulation of immune responses in infectious disease and autoimmunity. International journal of hyperthermia: the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group, 34(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2017.1411621

Galli, F., Lai, C., Gregorini, T., Ciacchella, C., & Carugo, S. (2021). Psychological Traumas and Cardiovascular Disease: A Case-Control Study. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 9(7), 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070875

Huffhines, L., Noser, A., & Patton, S. R. (2016). The Link Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Diabetes. Current diabetes reports, 16(6), 54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-016-0740-8

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2023, August 1). Chronic stress puts your health at risk. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20046037

Roatta, S., & Farina, D. (2010). Sympathetic actions on the skeletal muscle. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 38(1), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/JES.0b013e3181c5cde7

SCSASmithers. (2013, March 6). When the Body Says No -- Caring for ourselves while caring for others. Dr. Gabor Maté. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6IL8WVyMMs

Seok, J. W., & Kim, J. I. (2024). The Efficacy of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Treatment for Depression: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(18), 5633. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185633

Shapiro F. (2014). The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. The Permanente journal, 18(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-098

Somatic Experiencing International. (2014, October 15). Nature’s Lessons in Healing Trauma: An Introduction to Somatic Experiencing® (SETM). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nmJDkzDMllc

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, March 24). How your body controls breathing. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/lungs/body-controls-breathing

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2015). Chapter 1. Lessons from Vietnam Veterans, in The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books. ISBN-10: 0143127748

Disclaimer: Psychotherapy is a psychological service involving a client interacting with a mental health professional with the aim of assessing or improving the mental health of the client. Neither the contents of this blog, nor our podcast, is psychotherapy, or a substitute for psychotherapy. The contents of this blog may be triggering to some, so reader’s discretion is advised. If you think that any of my suggestions, ideas, or exercises mentioned in this blog are creating further distress, please discontinue reading, and seek a professional’s help.

Therapy Uncomplicated is a podcast that is meant to help people who feel alone and unsupported with their day to day struggles. We want to educate people on mental health and show it isn’t something to be afraid of. We provide the “whys” and the “hows” for a path to wellness. We are here to promote positive change by offering education and new perspectives that destroy stigmas in mental health, and encourage people to go to therapy.

Comments